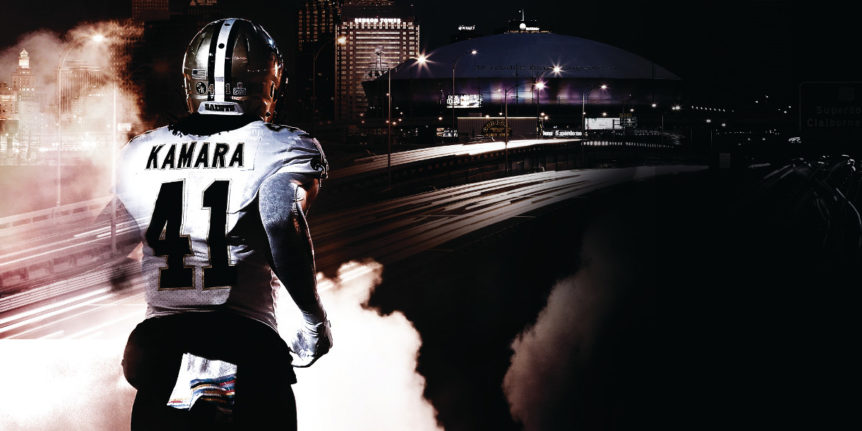

LIGHTS, KAMARA, ACTION

Through the French Quarter he walks. His legs are tired, body sore. But this is his town; these are his streets. From the bustle of the main drag that is Poydras Street down through Decatur and Chartres, Royal and North Rampart. Past the street corners where artists paint and magicians trick. He stops for photos, to talk and sign autographs. He looks in the windows of art galleries and boutiques. He observes cracks in the walls, but doesn’t run through them, instead ducking under the ornate archways and the wrought iron balconies around the streets in which he lives. Drifting home after another day at work.

Except Alvin Kamara doesn’t do work like everyone else. His office is the Superdome. He answers not to the managing director, but to the men and women who pack the stands from Metairie, Treme, Belle Chasse and all across the Bayou. He’s the defending NFL Rookie of the Year and the heir to the throne of the city of New Orleans.

And, after each game, he simply likes to walk among the people. His people. “I’m not looking for attention when I’m walking,” he tells Gridiron. “We leave the locker room, me and whoever it is that came to the game. Family, friends, and we just walk.”

Nineteen years previously, these same French Quarter streets had belonged to another dreadlocked running back, Ricky Williams, whose former apartment isn’t far from where Kamara now lives.

They are, in some ways, kindred spirits, sharing similar traits of eccentricity. They’re also intelligent free spirits who tread differently on the path to enlightenment. When Gridiron puts it to the former Tennessee Volunteer that they’re inextricably linked because of who they are, the position they play and the way their personalities occasionally cross over, he politely declines to answer.

Understandable, too, because – for all the similarities are obvious – so too are the key differences.

Kamara likes nights out with friends and family; Williams preferred solitude to fight his demons. There’s still a red flag that goes up when you compare anyone to the former Longhorn because of his off-field indiscretions and what happened in the Crescent City, a place he loathed, one that Kamara now loves. “There’s a lot of love here,” the second-year man adds. “A feel-good vibe in this city. A lot of good food, a lot of stuff to do. I’ve really been chilling, though, honestly. I try to hit all of the food spots, but I don’t really do too much.”

It’s the second time we’ve spoken to Kamara, almost 12 months to the day of our first conversation. Then, in the locker room after victory against the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, he spent four or five minutes proving himself engaging, forthcoming, erudite, and entirely comfortable in his own skin. It was nine games into his remarkable rookie season and he’d just piled up another 152 total yards and two touchdowns on his way to 1,554 from scrimmage. He also had a fumble which didn’t ultimately prove costly, yet Kamara was remarkably mature. “We’re human,” he says. “It happens. Nobody’s fault but my own. I’m just glad I wasn’t thrown to the sidelines after it. You do all you can to make sure it doesn’t happen, but I just had to move past it. You’ve got to have a short memory with things like that. Mark [Ingram] had two last week and I had that one today. We’ve just got to get better.”

Compare that to Marshon Lattimore, the cornerback who’d end the season as an All-Pro. On this day he’d become embroiled in a fight with Tampa’s Mike Evans that saw the receiver ejected from the game. Unlike Kamara, he’s surly and monosyllabic, constantly checking the three mobile phones that he has in his locker. A matter of a few yards separates these two rookies, yet the chasm between the personalities feels much, much wider. Kamara is mature and wise. Lattimore, at least on this occasion, is not. Between the two of them is Mark Ingram, who’s yukking it up with veteran receiver Ted Ginn. He has an afro comb in his hair, tattoos covering his chest and arms. He points at his understudy, and he and Ginn laugh as we start to talk.

“How have you been able to settle so quickly?” we ask.

“It’s support from my teammates,” says Kamara, pulling on a black t-shirt and laughing in their direction. “Drew [Brees] helps me so much. Helps me get settled in, the different schemes, things like that.” He stops and looks up at Ingram who’s still holding court. “And Mark, man,” he says, smiling again. “Mark’s been big. He helps me with reads, pass protections, anything. It’s been pretty easy because of those two guys. I’m just blessed to be in this situation.” Blessed indeed. Not every rookie gets a Hall-of-Fame quarterback and Heisman Trophy winner as backfield mates.

“The relationship with Mark….is that big brother, little brother?” we put to him. But before we can finish he interrupts enthusiastically. “Yeah, yeah man. Absolutely. Period. And it goes both ways. I’m his biggest fan when he has the ball. Just having him there as a vet, as a friend. He knows what’s going on. Just to have him there to help me has been so big.” Ginn and Ingram are still engaged in horseplay and Kamara laughs as he watches them and, in this moment, on this day, it’s somehow easier to imagine away his success as a by-product of his surroundings, of Sean Payton’s offense, of Brees and Ingram.

But that would be to doubt his impact as a player and personality. And, as his route to the top – complicated and, until now, nomadic – proves, you should never doubt #41.

For many people, life is all about finding your place, and that’s arguably what happened to Kamara last year. By his own account, the bright lights of the Big Easy shone luminously. Late-night trips to roped-off VIP areas, the trappings of fame. In an interview with Bleacher Report, as he drank shots with Falcons running back Devonta Freeman, Kamara said: “I just do what I do. Of course, I’m not just out here doing crazy stuff. I’ll just say I’m not scared to be me. How they take it is how they take it.”

He lived the lifestyle of a successful young man in one of the world’s greatest cities. And why wouldn’t he?

His story up until that point had been one of doubt, of being overlooked. His father was in and out of his life as a child and eventually disappeared during Kamara’s teenage years. He hasn’t had a relationship with him since. When the Saints travelled to Tampa for the rematch last December, Kamara’s father turned up unexpectedly and waited outside the visiting locker room. Kamara kept walking, ignoring his repeated attempts to get a response, and then boarded the team bus. “Didn’t even look at his ass,” he told Bleacher Report.

When Gridiron asks about that period of his life, he changes emphasis quickly. “Growing up in Atlanta made me mentally strong and gave me some real grittiness. I’m more into the way it’s going to be, no matter what the perceptions are.” Perceptions can be interesting. His demeanour belies the fire inside of him and the anger he had. And still has. Look at the perception of him as a pro: brilliant, graceful, exuberant, mature. Contrast that with the mentality of his collegiate days.

One of the nation’s top running backs out of high school, he signed with Nick Saban’s Alabama believing he was the perfect fit. He expected to play straight away; to be a star. All despite a backfield that included Heisman winner Derrick Henry, T.J. Yeldon and Kenyan Drake. Observers of that time told Gridiron that he believed he’d “earned the right to act as he pleased”.

He never played a down. “I just feel like he couldn’t be himself at Alabama,” his sister Momolu told Sports Illustrated. “Look at Alvin now. Now think about Alabama players. He wasn’t going to evolve to that, not at Alabama. It wasn’t going to happen. I think he sensed that he couldn’t be himself there, and I think that’s what really triggered it.” His stay in Tuscaloosa was shortlived and littered with mistakes. First, Kamara and some teammates purchased BB Guns and shot up a delivery driver, a Waffle House window and the school’s engineering building, causing $3,000 worth of damage. Then, during July 4 celebrations, he set off fireworks in his dorm doorway, sending smoke spiralling through the corridors and setting off the fire alarms. On the field things weren’t much better. He suffered a knee injury in practice and was forced to redshirt. The curious and frustrated mind couldn’t rest easy.

He bolted for freedom, only to be arrested. It was crossroads time. The road more travelled beckoned. The one so many talented young athletes choose. A name in time, prefixed with the words: ‘I wonder what became of…’. Instead, he chose the road less travelled, packing up and heading to Kansas where Hutchinson Community College lay at the end of his yellow brick road. So, what did a year with the Blue Dragons teach him about life and about being Alvin Kamara? “Just being wiser, I guess,” he tells Gridiron. “And knowing how to deal with people, knowing how to get things done on the field and off it. Dorm, practice, class. That same triangle. I didn’t do nothing else. And I knew I had to get it right. I knew I had to show everybody that I could do the things they thought I could.”

Humbling? “Humbling.”

He went back to the SEC and Tennessee. He worked hard, but was mainly a backup, spending most of his time with the Volunteers in a complementary role to Jalen Hurd. Intent on declaring for the draft without the on-field resume to propel him into the early rounds, he stayed, emerging as a dynamic scoring threat, scoring 23 touchdowns on just 284 touches, ending up as the 67th overall pick.

“I think you’re always in the business of looking for someone like that,” said head coach Sean Payton after drafting him. “There’s only a handful of players you just have a clear vision for and he was one of those guys, extremely smart and versatile.” It was a system that fit him to a tee. And a quarterback who could inspire him towards greatness. “Man, Drew is incredible,” he tells us. “It’s different when you’re watching him from afar, on TV. Like, ‘Oh my gosh that’s Drew Brees’. He’s so good. When you see him in person you understand why he’s so good. Every day it’s the same thing. He’s a model of consistency, from his warm up to… just everything. Our relationship is super good.”

Twelve months on from our first chat, Kamara feels a little different. Where once he was relaxed, now Kamara seems more guarded. Reticent to open up. Protected. “Were you surprised by what you achieved as a rookie?” Gridiron asks. “I pretty much did everything I wanted to do,” he shoots back.

“Do you worry you might not hit the same heights given you had one of the greatest rookie campaigns in NFL history?” we continue… “I just do what I do. I’m not too worried about that.”

And rightfully so. On the field in 2018 he’s exactly the same player: Electric. Off it, he may have changed; his personal wall seems higher than before. But Kamara still retains some of the eccentricities that set him apart from the norm. And that’s to be celebrated as much as a touchdown, especially in an era where an athlete with a brain and voice is seen as a threat.

It’s easy to disappear into the throng on the streets outside the Superdome after a ballgame, to lose yourself in the melee of cabs and crowds, of tarot readers and trumpeters. The scene after victory is carnival-like, and you wonder what it must be like for fans when their hero strolls past. “I might as well walk,” adds Kamara. “It’s easier. It just makes sense.”

You could say the same about him being in this vibrant, magical city. There’s no place like home, and Alvin Kamara has found his.

This article originally appeared in Issue XLII of Gridiron magazine – for individual editions or subscriptions, click HERE