The Pioneers

On October 23, 1945, the Brooklyn Dodgers signed Jack Roosevelt Robinson to a contract with their top minor-league team, the Montreal Royals. After a racially-charged spring training with the Dodgers in Florida, Robinson made his Royals debut in a game at Jersey City, and went on to win the MVP award in the International League, as well as being a fan-favourite in Montreal. Then – on April 15, 1947 – Robinson made history by breaking the colour barrier that had held sway since Moses Fleetwood Walker stopped playing in 1889.

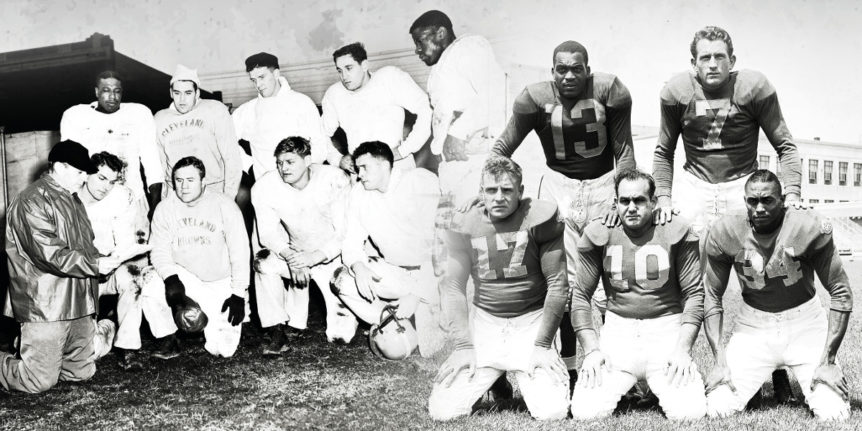

By the time Robinson ended baseball’s apartheid, four players had already integrated professional football. That more has never been made of Kenny Washington and Woody Strode of the NFL’s Los Angeles Rams and Bill Willis and Marion Motley of the All-American Football Conference (AAFC) Cleveland Browns is down to a number of factors, not the least that baseball, in the immediate post-war era, was America’s National Pastime; its position as yet unchallenged by the advent of television and growth of pro football. Indeed, college football was the bigger, more glamorous game – and already integrated in most of the country apart from the South.

Yet the story of those Four Horsemen of Racial Equality is an important one, and it ties into Jackie Robinson’s own tale rather neatly.

The last two black players, in 1933, were Ray Kemp, a big tackle out of Creighton who wasn’t played very much and took a coaching job instead, and Joe Lillard, a very talented tailback with a habit of taking no abuse from white players. This made him a liability: think of Branch Rickey’s famous test for Robinson, to see if he could take the abuse without retaliating. Lillard would later star on some semi-pro teams, most notably the Harlem Brown Bombers.

In 1939, Robinson entered UCLA after two years at Pasadena Community College. You could argue baseball was the fourth best of his sports: he was a star running back, basketball player and national Junior College long-jump record holder. His 7.78m mark in the latter wasn’t bettered for decades and broke that set by older brother Mack, a silver medallist at the Berlin Olympics behind Jesse Owens in the 200m. Had there been a 1940 Olympics, and Robinson trained more for track, he would have been a medal contender.

But, in 1939, Robinson had bigger fish to fry. He joined a strong UCLA team that already boasted Washington and Strode, and led them to an undefeated 6-0-4 season. Washington was the star tailback; his career-record 9,975 yards of total offense wouldn’t be broken for 56 years. Strode was a blocker, and Robinson the one who broke big plays. They were dubbed the Gold Dust Trio, after the Gold Dust Twins, who were a racially-insensitive pair on the label of the popular brand of flour.

In their final game of the season, the Bruins drew with USC, also unbeaten but with only two ties. You can see some film of the game that shows you Robinson’s running style and Washington’s incomplete pass on fourth and goal that sealed the game. Why UCLA coach Babe Horrell didn’t let Robinson kick a field goal (yes, he was the kicker too) and win the thing is something you’d have to ask him.

Without Stode and Washington, UCLA went 1-9 the following year. In 1941, Robinson was playing semi-pro in Hawaii for the Honolulu Bears, leaving just before the attack on Pearl Harbour. He played a few games for the L.A. Bulldogs in the Pacific Coast Football League, which was of a pretty high standard, alongside Washington and Strode, as well as semi-pro basketball for the L.A. Red Devils. After the war, he would play baseball in the Negro Leagues for the Kansas City Monarchs, from whom Rickey grabbed him, without compensation, for the Dodgers.

In 1946, the NFL’s Cleveland Rams moved to L.A. intending to play in the Coliseum, which had been built by the city for the 1932 Olympics and was run by the city. But campaigners in L.A., led by sportswriter Halley Harding of the L.A. Tribune, argued that black men fought for their country and, if a pro football team were going to use a municipal stadium, they ought to be integrated the same way high-school and college teams were in California. So the Rams looked around and signed the two former UCLA legends: Washington and Strode.

Pro football – 13 years after the implementation of its unwritten segregation policy – became integrated once more.

Strode made less of an impact on the gridiron, but is the most recognisable of the four black pioneers. You’ve seen his face, a handsome mix of black and Native American ancestry, in many Westerns, most notably the title role in John Ford’s Sergeant Rutledge; as Pompey in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valence; in The Professionals, and in a small-but-crucial part in Sergio Leone’s Once Upon A Time In The West, as one of the three killers waiting for Charles Bronson to get off the train.

Strode was a dynamic athlete, who competed in the decathlon and whose portrait was part of the exhibition by Hubert Stowitts banned by the Nazis at the Berlin Olympics. After UCLA, he also played in the PCFL, while working for L.A. District Attorney’s office as a process server, and for a base team in the army during the war. Strode began his film career at the same time: he plays Eddie ‘Rochester’ Anderson’s chauffeur in Star Spangled Rhythm.

His two-way skills didn’t translate easily into an NFL that was becoming more specialised; by 1948, he failed a tryout for the Brooklyn Dodgers (another coincidence) of the AAFC, but played for the Calgary Stampeders of what was then the Western Interprovincial Rugby Union; the Stamps won the Grey Cup that year. He began wrestling in between movies, and once formed a classic black tag team with Bobo Brazil. Strode had a long movie and TV career, often playing ‘natives’ of various sorts in things like Ramar of the Jungle or Jungle Jim, but also in big movies like The Ten Commandments and Spartacus. After Leone, he had a decade of playing leads in European movies, then came back and was always busy; his last film role was in Sam Raimi’s exploitation western The Quick and The Dead, relased a year after his death in 1995. Strode supposedly did 1,000 push ups every day; his wife Luana was a descendant of the last queen of Hawaii.

At 6ft 2ins and 210lb, Willis was a small nose tackle (or middle guard by the 1940s’ standards). He went to Ohio State primarily as a sprinter, and it was his quickness off the line of scrimmage that made him such a force inside. Willis was also able to stand up and drop back in pass coverage; although Bill George is considered the first middle linebacker as we know it, you could argue Willis often served that function.

Although he played high school ball in Columbus, Willis required a letter from his coach to Brown, after a year of working, before earning a chance at Ohio State. While there, he played for a 9-1 National Championship team for Brown. The following year, Brown lost many players to the military so, after a 3-6 season, he went too; in 1944, Willis led the Buckeyes to 10-0 and was the outstanding player at the College All-Star game.

With no option in the segregated NFL, Willis took a job in 1945 coaching at a black university, Kentucky State. In 1946, he called Brown, asking for a tryout in the new league. He didn’t hear back, and was about to sign with the Montreal Alouettes when Brown, through a journalist, passed on a message to try out. Willis was All-AAFC in each of the league’s four years (the Browns won all four titles).

In their first NFL campaign, the Browns finished 10-2, with both losses to the New York Giants, but had to face them in a playoff to go to the championship game. Wearing sneakers on the icy field in Cleveland, Willis sacked Charley Conerly for a safety and then somehow caught Giants running back Gene ‘Choo Choo’ Roberts from behind in the open field to preserve an 8-3 win. The Browns would defeat – guess who? – the Rams 30-28 to win the title in their first year. Willis retired after eight seasons, reaching a championship game in every one, to go into youth work in Ohio, where he had a long career at the state-wide level.

Motley was a big, almost-lineman-sized fullback who wore number 76. He played high school in Canton, Ohio and went to Nevada, before representing Brown at Great Lakes. In his final game for the Bluejackets, after he was eligible for discharge, Motley starred as they defeated Notre Dame 39-7. Brown turned down Motley originally, reportedly saying “I have enough fullbacks”, but then invited him to try out for the Browns after signing Willis. Speculation always has been that he somehow didn’t value Motley’s play as much as it probably deserved, but needed a second black player to room with Willis on the road. Interestingly, in 1946, Brown left Willis and Motley behind when the Browns travelled to play the Miami Seahawks although, on another occasion, he stood up to a hotel who originally refused to accept the two black players.

Motley was recently named to the NFL 100 Team, earning rave reviews from Bill Belichick as a powerful runner with some quickness; less a Larry Csonka battering ram than a Brandon Jacobs or Christian Okoye with more skill. His ability to play linebacker was another bonus. But Willis was also stoppable in some games and, like other fullbacks of the era (Tank Younger, John Henry Johnson), suffered statistically because of the way carries were shared. Motley was first-team All-Pro only twice, once in each league, but featured on the NFL’s all-decade team of the 1950s despite retiring in ‘53, alongside Willis.

Motley’s relationship with Brown was problematic; despite frequent requests, he never gave his charge a job as coach or scout. It would seem something in Motley’s make-up didn’t appeal to Brown. Other star players left the team, most notably end Mac Speedie (who was white) in 1953 and played three years in Canada. He claimed he was never sufficiently obsequious to Brown, and once brought a skunk named ‘Paul Brown’ to practice.

But whatever Brown’s personality, his commitment to putting the best players on the field was, in its way, a much-needed statement of equality, just as much as the Rams’ was in reflecting the feelings of an integrated community. Motley went into the NFL Hall of Fame in 1968, a year after Emlen Tunnell became the first black inductee, and three years ahead of Willis. Washington is in the College Hall of Fame, and Woody Strode, well, he ought to have a star on Hollywood Boulevard.

All four should be remembered as a disparate group who played the game they loved and were the first to integrate big-time American pro sports.

TIMELINE OF RACIAL INTERGRATION AND ACHIEVEMENT IN NFL

1902 Charles Follis becomes first black pro footballer (Shelby Blues/Ohio League)

1920 Fritz Pollard (Akron Pros) and Bobby Marshall (Rock Island Independents) among first black players in APFA (later to become NFL)

1921 Fritz Pollard becomes first black head coach in NFL (Akron Pros)

1923 Fritz Pollard becomes first black QB in NFL (Hammond Pros)

1920-26 Nine black players feature in NFL (including future actor/singer Paul Robeson)

1929-33 Great Depression hits USA

1933 Joe Lillard (Chicago Cardinals) and Ray Kemp (Pittsburgh Pirates) are last black players to appear in NFL

1934-45 Segregation in the NFL, believed to be at behest of Washington owner George Preston Marshall

American Association (New York) and Pacific Coast Professional Football League continue using black players

1946 Kenny Washington and Woody Strode signed by NFL’s Los Angeles Rams, while Marion Motley and Bill Willis by Cleveland Browns of the All- American Football Conference

1947 Jackie Robinson becomes first black player in Major League Baseball with the Brooklyn Dodgers

1948 Mel Groomes and Bob Mann signed by the Detroit Lions

1949 George Taliaferro becomes first black player drafted into the NFL, but opts for the AAFC’s LA Dons over the Chicago Bears

1950 Chuck Cooper (Boston Celtics) and Nat ‘Sweetwater’ Clifton (New York Knicks) become first black players in the NBA

1954 Joe Perry (RB, San Francisco 49ers) becomes first black player named NFL MVP

1960 Gene Mingo (Denver Broncos) becomes first recognised black NFL placekicker

1962 Washington Redskins become last NFL team to sign a black player (Bobby Mitchell)

1967 Emlen Tunnell (NY Giants/Green Bay Packers) becomes first black player elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame

1968 Marlin Briscoe (Denver Broncos) becomes first black player to regularly start at QB

1987 Doug Williams (Washington) becomes first black QB to start – and win – a Super Bowl

1989 Art Shell (Oakland Raiders) becomes first black NFL head coach since Fritz Pollard

2003 Rooney Rule introduced, compelling teams to interview racial minorities for head coach and, later, other senior roles

2006 Warren Moon (Oilers/Vikings/Seahawks/Chiefs) becomes first black QB elected to Pro Football Hall of Fame

2013 Black players are reported to dominate key positions such as CB and RB in the NFL

2014 Survey reveals that 68% of players in the NFL are of African-American heritage

2017 New York Giants become the last of 32 NFL teams to start a black QB, as Geno Smith ends Eli Manning’s 210-game streak

Survey reveals that while 70% of NFL players are black, only 25% play QB

This article originally appeared in Issue LI of Gridiron magazine – for individual editions or subscriptions, click HERE