Every Breath You Take

Everything Laviska Shenault does is because of that night. Every run, every catch, every route, every step. Every breath.

Every last breath.

The mountains that surround Boulder are his escape. Their snow-capped peaks a world away from southeast Irving where he grew up; away from Highway 12 and the moment that changed his life forever.

It’s the last day of August 2018 in the beautiful city of Denver. The temperature hovers in the high 70s (Fahrenheit) and there’s a hint of rain in the thin air that pervades. The 90th Rocky Mountain Showdown is into the third quarter and, although Colorado lead their in-state rivals by 17, the Colorado State Rams are beginning to gain a foothold and have forced the heavily favoured Buffaloes into a third-and-14 at their own 11.

Quarterback Steven Montez has the offense in 10 personnel – a ‘back and four receivers – with seniors Juwann Winfree and Jay MacIntyre outside to the right and true sophomore Shenault in the slot. At the snap, cornerback Anthony Hawkins blitzes, leaving the 6ft 2in, 215lber uncovered. He runs alone to the 17 and stops, pivoting back towards his signal-caller just as the ball arrives. Shenault grabs it and turns upfield as the middle linebacker closes in to keep him short of the line to gain. But the wideout has other ideas, turning on the jets and accelerating out of the ankle tackle. Next up is the free safety who has the angle at the 30 – but Shenault accelerates again, leaping over him and turning upfield to daylight.

Gone.

The whole play from snap to end zone takes 13 seconds.

Game.

Shenault has covered the 40 yards from his own 35 to the Rams 25 in 4.08 seconds on the way to an 89-yard touchdown. No receiver has ever run that fast at the NFL Scouting Combine. No player has.

On this night the Mile High City would be his to the tune of 11 catches for 211 yards and two scores, four more grabs than he had his entire freshman campaign. ‘The Secret’ that Buffs coaches and players were aware of in the spring and summer had now been unleashed on the nation. Laviska Shenault is for real.

Shenault was born in the Lone Star State into an athletic family, one fuelled by a love of competition. Mum Annie played college basketball and still holds records for points and rebounds per game at the University of Dubuque, a Division III school in Iowa.

His father, Laviska Sr., was a high-school football star of some repute and the pair would play sports for hours with their six kids, be it four-on-four basketball or flag football with Annie at quarterback, until the daylight became dusk became dark. Once inside the Miami Dolphins-themed house in the Glenn Heights neighbourhood of suburban Dallas, Laviska and his father would play Madden, then practice plays they liked from the video game in real life. Hour after hour, day after day, week after week with Laviska Sr. throwing passes, always as his hero Dan Marino. However, Jr’s hero is from Foley, Alabama, all long limbed and graceful. He doesn’t mind if Marino is under centre, as long as he can be Julio Jones. There are distinct similarities too: size, speed and physicality are all on point. At times you could be watching a young Julio.

Jones’ path to the NFL was mapped out at an early age. Even in the football factory that is the Yellowhammer State, he was head and shoulders above the rest. For Shenault, the road has been slightly different. A late bloomer, he was considered only a three-star prospect by most of the recruiting services.

“He wasn’t a guy that you naturally looked at and thought would be great,” his former position coach, Bam Harrison, tells Gridiron. “He only caught a handful of passes as a junior but really grew into his body his final year and then broke out.” Identifiable on film by his dreadlocks that fall well below his shoulders, he was dominant, with 46 catches for 825 yards and nine touchdowns, helping his team to a 16-0 record, its first state title and second spot in the MaxPreps national rankings. He was also focused: his hair prevented him from playing basketball because of a code enforced by the DeSoto High boys’ coach. “We didn’t have a hair policy,” laughs Harrison. “It was football all the way for him.”

The recruiting battle for Shenault didn’t hit full stride until later than usual but, as he developed, so did the intensity of the chase. Interest ranged from minnows such as UTSA, North Texas and New Mexico to powerhouses like Texas A&M, LSU, Oklahoma and Alabama. Les Miles and Nick Saban came on house visits but, in the end, he chose Colorado, in part because of the relationship built with offensive coordinator Darrin Chiaverini and in part because of the solitude that Boulder offered this shy young man who once admitted that he didn’t want to play quarterback in youth football because he was “too scared”. “I wanted to go somewhere not on the map,” he says.

Chiaverini is the man who’s credited with turning Shenault from freshman afterthought to sophomore sensation. Jack Barsch of Ralphie Report, the influential Buffaloes fan-site, says once it became clear what the team had on its hands, it needed a creative mind to get the best out of him. “We were always aware that Viska had the physical traits to blow up,” he tells Gridiron. “However, when some of the information about this summer’s practices and the strength and conditioning workouts came out, it pushed the hype to a new level. Coach Chiv tailored a lot of the offense around Shenault’s unique skillset and it’s worked wonders.”

In the spring of 2018 as Chiaverini watched his talented young receiver dominate practice after practice, he began that process of tailoring: devising different ways to get him the ball. Meanwhile, Shenault continued to turn heads like few on campus ever had. “He’s special. Viska’s a freak,” his quarterback Steven Montez, himself a potential NFL draft prospect, told local reporters after yet another session in which No. 2 toyed with defenders. “This is kind of a crazy comparison, but he reminds me of LeBron [James],” he added. “Coach has his hands full trying to get him the ball.”

In his office, Chiaverini reviewed the tape of each day’s sessions and wondered how to use an athlete with 4.4 speed who could move like a tailback, run routes like an NFL receiver and block like a tight end. In high school Harrison had created a package of plays called ‘Hawk’, designed to get Shenault the ball as often as possible. Chiaverini needed something similar – although his plan was a little more rough around the edges, at least on the name front. “I came up with the title of ‘Let’s Just Play Him Everywhere’,” Chiaverini says. It’s worked. Viska has been a tight end, wide receiver, slot receiver, a tailback, wing-back, H-back and quarterback in the Wildcat this season. All with remarkable success.

Before a third-quarter foot injury against USC in mid-October, he was beginning to feature strongly in the Heisman conversation as he weighed in with one great performance after another: 126 yards receiving against UCLA, 127 versus Arizona State. Touchdowns in every game, rushing scores, receiving scores. The only thing he hasn’t done is thrown for a score.

Yet.

Alabama’s Tua Tagovailoa looks to have the inside track on the Heisman, but Shenault has a legitimate claim to be in New York for the ceremony. Winning the thing? That might be more difficult, according to Barsch. “I think he has the talent to (do so), but I don’t know if a wide receiver can win the Heisman in the modern era. The award skews towards quarterbacks and for good reason. As good as Laviska is, Tua is coming back next year, as is Trevor Lawrence and Justin Herbert. He should be in the conversation, but I’m not getting my hopes up.” And the last receiver to win the award back in 1991, Desmond Howard, agrees: “Not enough touches,” he tells Gridiron. “Definitely comes down to a lack of touches. But he’s special.”

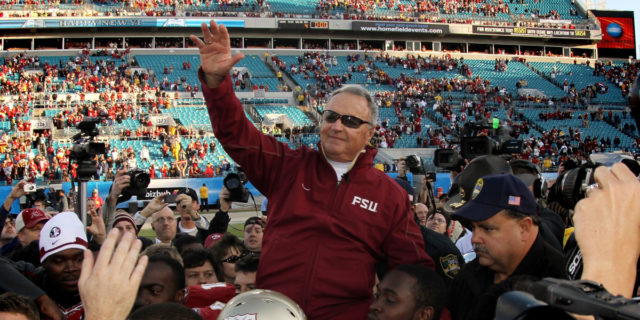

Howard isn’t the only one who believes he’s uniquely gifted: after the win over the Bruins, Chip Kelly called him the best receiver in a Pac-12 loaded with explosive players, while former CU coach Gary Barnett claimed that Shenault was the best player to wear a Buffs helmet in 30 years. Praise indeed when you consider some of the names to have donned the silver, black and gold during that time: Eric Bieniemy, Darian Hagan, Kordell Stewart, Chad Brown, Alfred Williams and receivers Michael Westbrook and Mike Pritchard to name but a few.

Pritchard, who was part of the Buffs’ only National Championship back in 1991, has been fulsome in his praise. “He’s just a pup, but he’s awesome. Beast,” he tweeted after the sophomore burned Nebraska for 177 yards receiving in the upset win in Lincoln. “It’s interesting you mention those last two wideouts,” Barsch says. “I think Laviska plays like a combination of the pair. I’m not saying he’s as good as those two legends yet, but he certainly has the potential to be a generational talent. I would bet that he leaves his name all over the school record books before he’s done.”

But Howard warns against getting too carried away, despite all the evidence to the contrary. “I honestly believe it’s way too early to tell if he’s generational. Like I said, he’s special, but I don’t throw the term “generational talent” around casually. In my opinion, there are very few players at any position who fit that description.”

As someone who’s been there and done it, what advice would he give Shenault as the noise around him gets louder and louder? “It’s important to keep your circle tight,” he tells us. “Listen to the voices that helped guide you to where you are now and try to block out the rest. Don’t get caught up in the hype or even the inevitable criticism that comes along too. Being a creature of habit is helpful. Maintain the same study schedule and practice habits.”

So is it more difficult for players to do that these days than it was when Howard was winning a Heisman in Ann Arbor? “Absolutely it is. It takes greater self-discipline when every person who follows you on social media essentially has access to you and the ability to get in your head if you allow it.”

Which is why Shenault is so comfortable among the red rooftops of Boulder, the town that’s been dubbed ‘the city nestled between the mountains and reality’. “It’s a great fit for him culturally,” Barsch says. “It’s a college town but it’s not necessarily a college sports town. I’m sure he’s reached a new level of celebrity, but CU is also a place where athletes like him get to be normal college students more often than not. I’m sure that level of normalcy is comforting to a player as humble as Laviska.”

He may well be humble in lessons and walking the streets of the city but, when the game starts, Shenault becomes something different. “We all have a dog mindset,” Shenault told reporters before the USC game in a rare burst of emotion. Understandable, too, because on the field, he’s certainly barking. Against Arizona State he’d score all four of Colorado’s touchdowns: two receiving, two running. Like a dreadlocked human highlight reel he slashes through the Sun Devils defense. A week later, in the national spotlight, he takes a snap from the Wildcat at the UCLA 49 and races through the defense to pay-dirt. “You think, ‘All right, he’s already played this well up to now, maybe he’ll have a slower game?’,” says Montez. “But he’s doing more and more crazy stuff and keeps getting better every game. That’s the scariest thing about him because you think, ‘What is he going to do this week?’”

For the ultimate football hermit it’s all in a day’s work. “I’m just going to keep being me,” he told reporters when asked of the Heisman hype. Right now this wide receiver slash tight end slash running back slash quarterback is just happy to be playing ball. His opponents? Just happy when the game’s finished.

“We couldn’t tackle him,” Arizona State head coach Herm Edwards said in his postgame press conference after Sheanult’s four-touchdown game. “We had him a couple of times. Even on the first series they threw him a little screen and we had him but then all of a sudden we didn’t. He broke the tackle and kept running.”

At times Shenault resembles more of a comic-book character than football player. Like a new Marvel creation with his ability to run, block, leap, catch and dominate, dreadlocks flowing, untouchable. “I think I’m either Incredible Hulk or Dr. Strange,” he tells reporters after practice one day. “Incredible Hulk’s extra strong, can barely be stopped, and Dr. Strange can pretty much do anything.”

Perhaps ‘Strangely Incredible’ should be the nom du guerre for the receiver who can do almost anything except be denied. When you watch him play you realise why this isn’t so far from reality. Yet every day he knows that there’s one thing that has defined him, one thing that’s beaten him, almost to submission. He may be unstoppable, but death is undefeated; as he knows all too well after that night…

Viska is ten years old, sat in the back of the car on the way back from a family barbecue. It’s dark now and his father is driving. He slows and pulls to a halt next to the bustling highway that wraps its way around the city of Dallas. A tired Laviska Sr. gets out to swap seats with his wife so that she can drive, walking around the front of the car. As he does he trips in the dull light and falls into the road, into the path of an F-15o. The pick-up hits him and flips him into the path of another car. He’s killed instantly as his family watch on horrified.

For every breath.

For every last breath.

This article originally appeared in Issue XLII of Gridiron magazine – for individual editions or subscriptions, click HERE