TREVOR LAWRENCE: A TOWN, A TEAM, HIS DREAM

The high-school football scene is awash every year with superstars of the future attempting to enjoy normal lives amid unfathomable expectations in their own town and the insane spectre of college recruiting. But sometimes, there are talents so great that the whole process takes on an extra level of madness. Gridiron heads to Georgia to meet the quarterback many claim is the greatest prep player of all-time…

The record, when it comes, is beautiful in its simplicity. An effortless post route dispatched with the sort of velocity that an 18-year-old arm shouldn’t be able to muster. In the immediate aftermath, the record-breaker, having just surpassed Deshaun Watson’s Georgia high-school mark for career touchdown passes, shows very little emotion despite his moment of history: a quick clap of his hands, a walk down the sidelines to greet his receiver and a gentle jog back to reclaim his seat on the bench.

Straightforward, clinical, cool.

Meet Trevor Lawrence. The No.1-ranked high-school player in the United States and arguably the greatest prep quarterback of all-time.

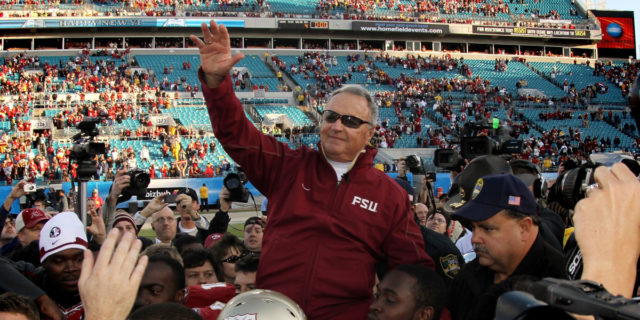

Head coach Joey King tells a story of when 24 coordinators and position coaches showed up on a single day during spring practice a couple of years back. He follows that up by informing Gridiron that tucked away in his office drawer are more than 150 business cards wrapped in an old rubber band. “They’re from all the college coaches who were here that spring,” he says. “They came from all over the country with one thing in mind.”

Sign the kid.

His offensive coordinator, Michael Bail, has a similar tale. “Have you heard about the time Alabama head coach Nick Saban landed his helicopter right here on this practice field? Same as Kirby Smart and Dabo Swinney. All here. All for Trevor.” So how old was he when Saban showed up, we ask? “Nearly 16,” says Bail about as matter-of-factly as humanly possible. “They knew how special he was. Hell, I’d known for years. Now the cat’s out of the bag and the whole world knows who he is and what he’s done here.”

‘Here’ is Cartersville, some 70 miles north of Atlanta. Home to almost 20,000 people, it was once the capital of the south for a time during the Civil War. It’s an unexpected gem in a region of the US ravaged by poverty and unemployment. Full of nice restaurants and independent shops, it’s got the sort of middle-class feel you’d expect around Martha’s Vineyard or Missoula, Montana. A busy railroad bisects the town. If a train’s going anywhere in the south then it goes through here. And you’ll know about it: the piercing whistle of the locomotives cuts through the thick air day and night. There are 17 churches in Cartersville. Eighteen if you count Weinman Stadium, where many of the town’s prayers are offered up. This is Coach King’s flock, but it’s Trevor Lawrence’s town.

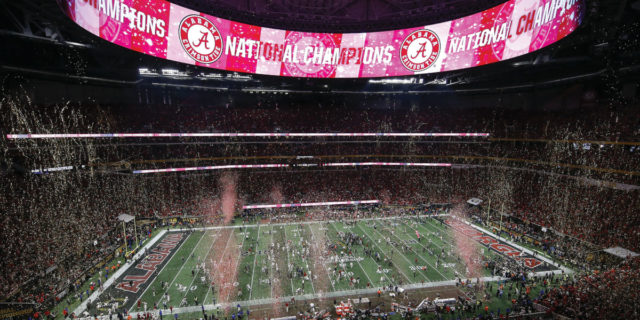

At least it is for one more night. Because this is his last hurrah. The senior has one more regular-season game left in the purple uniform before he heads east to try to win the job as the starting quarterback for the defending national champion Clemson Tigers, after one of the most competitive recruiting battles in years that saw the born-and-bred Georgian turn his back on the Bulldogs – a decision that didn’t sit well with many in the town.

Or the state.

“For a lot of people round here it was a big thing,” says Coach King. “And for a time, it became very difficult to manage. We just tried to tell him to take no notice, but it’s testament to the head on his shoulders that he ignored it. I think it was tough for him to get messages from people telling him he should die, especially as a 17-year-old kid. But man, he handled it extremely well.

“There’s been an awful lot of outside pressures. He’s just a very humble kid, very quiet, very low key. To me that’s really the part that continues to amaze me about him, someone of his status. A lot of people would let all that go to their head. But he’d rather not talk about any of that stuff, rather not do an interview, just get on with being a kid. And as a player, he lets that talent speak for itself.”

And what a talent. Throw on the tape and you see a very rare ability: 6ft 6ins, 210lbs with tremendous arm talent, accuracy and the ability to extend plays with his feet. His eyes stay downfield and he continually manipulates defenders. But can he lead? “That’s the area in which he’s really grown in,” says King. “He’s taken the team on his shoulders and it’s been so impressive to watch. He’s taken us to back-to-back state championships, and watching him lead his teammates has been incredible.”

As King and Gridiron walk to the practice field he tells us about his succession plan at quarterback, for the upcoming day when he can no longer call upon Lawrence. It’s all meticulously planned out down to the sixth grade, but the leading man knows that, despite being extremely young in coaching terms, he may never have another player like this. “Oh I totally believe that. He’s the best I’ll ever see. No doubt. One of the college coaches came through here and when he left he said to me that there were several NFL quarterbacks currently on rosters who aren’t as good as him. Think about that for a moment.”

He puts the whistle to his mouth and signals the start of the walkthrough. It’s the first Thursday in November and, the following night, King will lead his players against 8-1 Troup County – whose defense contains three or four SEC-bound players. As we take our seat in the stands, administrators drop by to talk about the school and what Lawrence means to this town. All are aware that they may never see his kind again.

By the time the conversation dies out, the backups are in and Lawrence is nowhere to be seen. He should be easy to spot: his shoulder-length blonde hair flows from beneath his helmet. But we can’t locate him. Just as we’re about to head back to the locker room we see him on the very far side of the field, sat against a wall spinning his helmet between his thighs and chatting to his offensive line. Then he is up, casually walking to see the first-team defense who’re gathered under a goalpost watching the last remnants of practice. He quietly high fives all of them, then wanders back as King signals the end of the session.

As the team crowd around and take a knee, Lawrence is back where he sat when we first saw noticed him, some 30 yards from his team. Aloof? Not a bit of it. This time he has gone to fetch the water cart and is wheeling it back to the pack. He kneels down, not at the front but on the periphery of the group, before casually walking to the locker room dragging the water behind him as he goes. It reminds us of what King had said an hour or so before: “His ability to be a normal high-school kid and really not make it about him is one of the most mature things I’ve ever seen.” And he was right. The most lauded prep prospect the south has seen since Herschel Walker? You wouldn’t know it.

As we walk back to the locker room, the distant strains of the school band can be heard over the players’ conversation. Drum majorettes are practising their moves on a strip of grass burnt by the sun and the patrons of the Capri Restaurant across the road from the school, a mecca for all things Cartersville football, queue for their gravy and biscuits and talk about how Trevor Lawrence is going to lead the Hurricanes all the way to state again.

Meeting the No.1 high-school quarterback in the nation is a strange experience. All of a sudden he is there, all 6ft 6ins of him. Gridiron actually takes a step back as he walks out of the locker-room door and shakes our hand. He is tall to the point of intimidating. We’ve been around plenty of NFL players over the years, and yet it feels like meeting a character from Game of Thrones. He’s huge, this ball of muscle, definition and throwing power. It’s easy to see why he looks so comfortable launching deep balls down the gridiron.

As we wander down to the field where Saban’s chopper touched down, he is as low key as advertised. So what keeps him grounded and how complicated has the process of choosing a university been? “It really hasn’t been too difficult,” he says. “Occasionally it got a little crazy but my coaches and parents have been great and so it’s probably been easier for me than a lot of people. Plus, my teammates don’t act like I’m anything special. I couldn’t do my job if they weren’t all doing theirs, so we just mesh.”

We chat for a few minutes about why Clemson: “The atmosphere there and the coaches which made it feel like I was part of a family.” And what he was looking for in a university? “I wanted to know why they wanted me and to be sure they knew what I was interested in.” And how close he is to Deshaun Watson? “We text back and forth quite a bit.” Occasionally he seems distracted, biting his lip and looking over his shoulder as his friends head home, but he’s polite, if a little guarded. As we wrap up and shake hands we ask him whether he’s ready for big-time college football? A smile breaks out on his face for the first time. “Yes sir, yes I am. I can’t wait.” We wish him luck against Troup County and away he goes, flicking his hair from his face. He has bigger fish to fry.

Starting with Troup County.

Tanner Glisson is the coach of the 8-1 Tigers of Troup in the small town of LaGrange, about a two and half hour drive from Cartersville. Responsible for turning a perennial doormat into a winner – Troup were 1-9 in his first season – he is fully aware of the challenge Lawrence offers his young team: they were on the receiving end of a 68-0 beatdown a season ago. And he’s spent a year trying to devise a plan to stop him doing the same thing.

But Glisson is also realistic about what he can achieve given the talent his young team will be going up against. “Playing Trevor… well… um…it’s a tough deal,” he laughs. “I mean, there’s only so much we can show him that he hasn’t seen before; we’ll try and mix it up but it won’t take long for him to work it out. One thing that was kind of unique we did this week in practice is have our scout team quarterback use miniature footballs because cornerbacks are always so surprised at how fast the ball comes out of his hand and it gets up on you so quick. I’ve coached more than two decades and I’ve not seen it come out like that. He’s just special; I actually think, at times, he gets bored because this level is too easy for him.”

We spend the afternoon with Glisson ahead of the game; at the team meal, the pre-arranged sleep time for the players, the bus ride to the stadium and the locker room pregame. His message is the same: “Why not us?” In the final moments before Troup take the field, he reiterates that point. His players are ready to bully the best quarterback in high-school football. “Our programme will never be the same if we win tonight. It’s gonna happen. Sooner or later they’re going to lose a football game. Why not us? Why not now?”

We can’t help but think back to what he said a few hours earlier, in the solitude of his office. “Listen, Trevor has a lot of God-given ability but from what I know about him, he works very, very hard to sharpen those abilities. He has all the intangibles. I mean, he’s Superman in a lot of ways because of what he can do. He’s the standard. He’s the benchmark. But our kids are excited to measure up. You want to compete against the best and tonight can turn into a story where one day you tell your grandkids when he’s a big star in the NFL that, ‘Hey I played against him and I got a tackle or an interception’. There’s no big recipe for playing a kid like this. It’s been 39 straight games where nobody has slowed him down, so…”

There are maybe 3,000 fans on hand at Callaway Stadium. Fans like Chris Derbuno who made the drive from Cartersville to watch Lawrence one more time. “Trevor’s been tremendous for our town. It’s been such an exciting run to win two state championships in a row. And it’s down to his ability as a whole. I’m amazed at how he handles the pressure of being the best and going to such a big school. And at every game this year we’ve had Clemson fans show up just wanting to see what they’re going to be getting next year.” And he’s right. Dotted around the stands are people in Clemson hats and t-shirts. No matter that they just won the national championship, bringing in arguably the best prep prospect the country’s ever seen means something to the industry that is major college football.

On this night the fans aren’t disappointed. Lawrence breaks Watson’s record and Cartersville pull away in the second half. But Troup keep it tight enough for him to play all four quarters, something he’s rarely had to do because the Hurricanes are usually way ahead. His play is patchy, but Lawrence makes a number of throws that take your breath away. After the game, we exchange hellos in between the surreal carnage of fans and opponents surrounding him for selfies and autographs; this, too, he deals with so naturally. As the crowd fades into the warm night, we walk with Coach Glisson to the buses and he reflects on what he’s just faced.

“It’s going to be really hard for him not to step onto the campus next season at Clemson and not be the best quarterback they have. I’ve some friends at a major SEC programme and I asked them last week to look for some of his weaknesses and they laughed and said there are none. And that’s from an SEC coaching staff.” He stops by the team bus and starts to climb aboard before turning and shaking hands. “Listen, I saw Deshaun Watson in high school a few times and they’re very similar. But Trevor has the bigger arm, the quicker release. And Deshaun was tearing up the NFL before his injury. It’s frightening to think what Trevor can become.”

As Gridiron gets set to leave Cartersville, we think back to a story that offensive coordinator Bail told us after practice the day before. About the time he knew Lawrence was special. “He’s playing a junior varsity game so it’s eighth grade and he gets the ball at midfield with 90 seconds left, down by five, and drops back but the pocket collapses so he just takes off. And 50 yards later he’s in the end zone to win it. But there’s a flag and it’s called back. He doesn’t sulk, he just jogs back to the huddle, calls the next play and away he goes again: 22-yard in for a first down, clocks it, then throws about the prettiest over-the-shoulder touch throw you’d ever see, to win it with six seconds left. And he’s playing junior varsity! You just don’t see kids do that sort of thing. You just don’t. He’s going all the way.”