Fight The Power

This article originally appeared in Issue LI of Gridiron magazine, back in 2019 – for individual editions or subscriptions, click HERE

As good as things appeared to be during the 1970s, unrest still simmered within the National Football League as the decade turned.

Players and owners were running low on patience with the league office as the 1980s began, prompting much legal wrangling as each attempted to secure a better future. On the field, meanwhile, there was a changing of the guard as the behemoths of the 1970s were swept away like an Etch-a-Sketch image.

One holdover persisted, for a few years at least, as the Oakland Raiders emerged triumphant as a wildcard team in Super Bowl XV – even if their victory was most notable for the spectre of ongoing wrangles over location that would have seen the Lombardi Trophy heading to Los Angeles if Al Davis had had his way. Improvement talks between the irascible Raiders owner and the Oakland Coliseum floundered over the subject of luxury boxes and, despite rival owners voting 22-0 against Davis’ move, he announced it anyway. The plan was met with multiple lawsuits – from the NFL, season-ticket holders and the city of Oakland as well as the Coliseum Commission – but Davis eventually got his way in 1982.

Franchises had relocated before – the Cardinals, Chargers and Texans/Chiefs all found new homes in the 1960s – but, with the door now jemmied open, the Raiders’ decision prompted others. By the end of the decade, the hapless Cardinals had continued their westward trek, from St. Louis to Phoenix, while the phenomenon’s enduring image remained the fleet of Mayflower Transit trucks pulling out of snowy Owings Mills, MD, in the dead of night.

Having also become frustrated by the lack of stadium development, Baltimore Colts owner Bob Irsay evaded state legislature that would have allowed the city to seize his team by fleeing to Indianapolis, which offered a new $77.5million Hoosier Dome, $4million training complex and financial considerations. Within eight hours of the arrival of the transporters – arranged by Indy’s mayor through one of his neighbours – the only trace of the Colts in Baltimore was fans’ tears.

“With the sides deadlocked, no games were played and television companies filled the void with hastily-arranged ‘all-star’ games and the Canadian Football League. Neither proved a success.”

The Raiders’ first season in La La Land would be a short one, but not through any shortage of effort on the field. Instead, the other tension bubbling beneath the veneer of the league erupted as a 57-day players’ strike – resulting from demands that wages be tied to gross revenues – wreaked havoc on the schedule.

With the sides deadlocked, no games were played and television companies filled the void with hastily-arranged ‘all-star’ games and the Canadian Football League. Neither proved a success, and there was palpable relief when players revolted against their own union to end the holdout. Negotiators eventually reached accord on a new Collective Bargaining Agreement in early December, increasing minimum pay and adding new medical rights as part of a guarantee from owners to provide $1.6billion in salaries and benefits over the agreement’s five-year term.

With so many weeks lost, the regular season was reduced to just nine games and playoffs expanded to 16 teams, with eight being drawn from each conference and seeded according to record. The Raiders topped the AFC at 8-1, mirroring the NFC’s Washington Redskins, but the two wouldn’t meet at the Rose Bowl, where Joe Gibbs steered his club to a first title in 40 years against the Miami Dolphins.

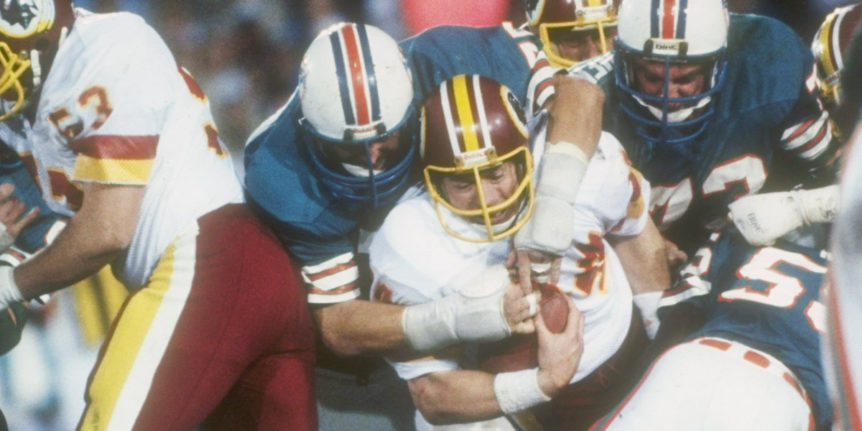

By strange coincidence, the Redskins’ next Super Bowl success came at the end of a 1987 season also affected by ‘player power’ as a 24-day walkout centred on the league’s free-agency policy briefly halted the on-field action after Week 2. While the games scheduled for Week 3 were lost, this time team owners responded by filling their rosters with replacement players, drawn largely from training-camp rejects and the ailing USFL [1], but widely derided as ‘scabs’ by fans and media alike.

Some 15% of NFLPA members eventually opted to cross picket lines, yet a perceived victory for the league only served to further erode public confidence. “If you’re going to have a labour disruption every five years, well, ‘labour disruption’ is an industry term’,” Bill Polian tells Gridiron. “When you translate that to the fan, that means that his favourite player is tarnished; his team is disrupted. We’re in business to entertain so, if you erode that bond between the fans and players, it becomes a disruption.”

The latest set of strikes created no immediate victors. It’d be years before the players finally enjoyed real free agency, while the league itself endured multiple black eyes at a time when schematic evolution meant its actual games were never more enjoyable.

“The 1980s were truly a time of innovation, from Bill Walsh’s ‘West Coast Offense’, to Don Coryell’s ‘Air Coryell’, Gibbs’ ‘creation H-Back’ and Sam Wyche’s ‘No-Huddle’.”

The 1980s were truly a time of innovation, from Bill Walsh’s ‘West Coast Offense’, to Don Coryell’s ‘Air Coryell’, Gibbs’ ‘creation H-Back’ and Sam Wyche’s ‘No-Huddle’. Yet no scheme attracts quite the same historical nostalgia as that which drove the Chicago Bears to their first championship since 1963 at the decade’s halfway stage.

The 15-1 Bears rumbled back to relevance in 1985, marrying Buddy Ryan’s ‘46 Defense [2]’ to an offense overseen by the star tight end from that ‘63 team, Mike Ditka. To say head coach and coordinator didn’t see eye-to-eye is an understatement, but it is Ryan’s record-setting D that is more widely remembered, with Hall-of-Famers Dan Hampton, Mike Singletary and Richard Dent leading the charge – and 330lb lineman William ‘The Refrigerator’ Perry winning hearts and games in equal measure.

Following their march through the postseason – in which the Bears allowed just 10 points across three games, all in their 45-10 Super Bowl XX win over the New England Patriots – it appeared the Bears would suitably carry the flame of their iconic founder following his passing in 1983. George Halas, the last surviving member of the NFL’s founding meeting in Canton, passed away from pancreatic cancer, aged 88, that October.

Yet the Bears’ 1980s ‘Monsters of Midway’ couldn’t match the dynastic feats of Halas’ 1940s immortals. Ryan departed for head-coaching gigs after their championship season and quarterback Jim McMahon was plagued by subsequent injury problems. Perhaps the greatest stumbling block to Chicago, though, was the fierce NFC competition provided by Gibbs’ Redskins, Walsh’s 49ers and a New York Giants team overseen by Bill Parcells and his brilliant defensive coordinator Bill Belichick.

Of all those great minds, it would be Walsh who left the biggest imprint on the decade. He signed off a stellar 10-season run in San Francisco after the 1988 campaign, with a dynasty-sealing third Lombardi Trophy tucked under the arm. His departure came amid other ground-breaking changes engulfing the entire NFL.

Within two months of Walsh’s departure, Pete Rozelle brought down the curtain of a highly successful near-30-year commissionership, while a little-known oil-man named Jerry Jones purchased the NFL’s most iconic club, the Dallas Cowboys. Collectively, those factors would combine to set the stage for the 1990s, in which new great teams emerged, damaging strikes stopped and, eventually, capricious franchise moves were avoided.

GRIDIRON GOLD

TRUMPING THE OPPOSITION

If the NFL thought merging with the AFL in 1970 would end the spectre of rival leagues, it thought wrong.

In fairness, the United States Football League was conceived as a complement to the establishment, to run in the spring when the NFL and college football hit their off-season. Attempting to go head-to-head ultimately proved to be its downfall.

The original franchise owners initially vowed to work within agreed spending limits but, without a hard salary cap, some couldn’t help themselves and teams soon ran into financial trouble. Things worsened amid bidding wars for big name players, with some teams prepared to take on the NFL in their thirst for a competitive advantage. The NFL wasn’t inclined to play nice either, which didn’t help when USFL franchises frequently changed hands and wanted to relocate.

The on-field product wasn’t bad, with future Hall-of-Famers scattered amongst the teams, but the USFL was doomed from the moment it – at the advocacy of one Donald Trump – voted to switch to a fall schedule in an attempt to force a merger with the NFL. Although an antitrust lawsuit jury ruled that the NFL had violated anti-monopoly laws, the USFL was awarded damages of just $1, which tripled under antitrust laws. The court’s decision was also the final play for the upstart league, which never reached its planned 1986 season.

This article originally appeared in Issue LI of Gridiron magazine, back in 2019 – for individual editions or subscriptions, click HERE