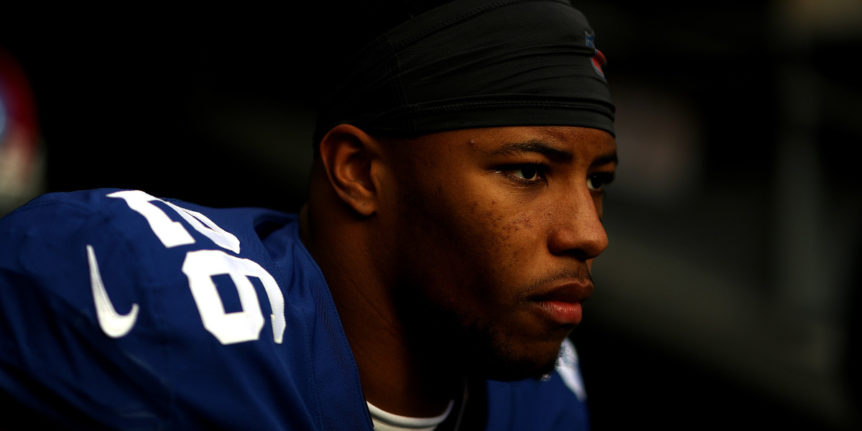

Taking it on the chin

This article originally appeared in Issue XXXVIII of Gridiron magazine back in 2018 – for individual editions or subscriptions, click HERE

When he was young, Saquon Barkley and his father Alibay used to walk to practice and games. Not because they wanted to, but because they had to. There was no car in the family so, if Saquon wanted to play, he had little option. They’d leave their red brick house on the north side of Coplay, Pennsylvania, squeezed between Gigi’s Pizza Grill and the sporting goods store, and walk down N 2nd Street, past Tony’s Hobby Shop and Lansky and Sons Auto, and into Hokendauqua, where N 2nd Street runs into S Front Street. There, next to the beautiful First Presbyterian Church, is Bob Warke Field, where Barkley fist made a name for himself. It was here that he won $100 from his father for scoring 15 touchdowns in a season on his way to becoming a star of the Eastern Pennsylvania Youth League.

But Saquon’s biggest moments came not on that turf, where now some old tackling dummies stand between two banks of rusted bleachers. No, the lessons that turned him into the best all-round prospect in this draft came on those walks. It was there he learned of Alibay’s addiction to drugs, his time in Rikers Island prison and both parents’ fight to keep the family together. And Saquon vowed that, no matter what, he’d work hard at being a good human being so as never to find himself in that situation.

“I knew he was going to be special when he started playing ‘ball. He was a very… a very adamant kid.”

It’s first-and-10 early in the third quarter of the 2017 Rose Bowl. The game is already turning into a classic. Barkley’s Penn State trail Sam Darnold’s USC 27-21 and they’re 79 yards away from re-taking the lead.

The next 16 seconds change everything forever.

Barkley takes the handoff and attacks the B-gap, but meets linebacker Uchenna Nwosu in the hole. Stopping on a dime, he cuts outside the defender’s grasp, then freezes defensive back Marvell Tell by stopping his feet completely and accelerating around him and heading towards the sideline.

Four seconds have passed. He’s gained half a yard.

At that moment, cornerback Ajene Harris approaches. Barkley sticks his foot in the ground and cuts back inside him before turning on the jets and running between Adoree Jackson and linebacker Cameron Smith. Five yards later, CB Jack Jones slides in front of him and Barkley cuts back inside again, then once more between safety Chris Hawkins and Smith. He evades a desperate, diving Porter Gustin at midfield and suddenly, finally, hits daylight. He’s evaded eight tacklers in nine seconds of mind-blowing running. Seven seconds later, having outrun Jackson, he is in the end zone. America is awestruck. It’s one of the most electrifying plays in a generation. Tough, powerful, strong, fast. It’s as balletic as it is explosive. It’s as beautiful as a butterfly, as devastating as a knockout punch.

And it, too, was forged on one of many walks along the streets of Coplay. And by a family history that set Saquon Barkley on the path to greatness.

“I knew he was going to be special when he started playing ‘ball. He was a very… a very adamant kid,” says Iran Barkley from his home in the Bronx. Iran, too, was once a sporting God: a three-weight world champion at middleweight, super-middleweight and light-heavyweight whose two victories over Thomas Hearns in Las Vegas and epic 12-round defeat to Roberto Duran in Atlantic City are remembered as three classics of a boxing generation that contained the likes of Sugar Ray Leonard, Julio Cesar Chavez and Marvin Hagler.

He isn’t the raconteur he once was, his speech slow and measured. Occasionally, two words run into one. But there’s a balance to his voice when he talks about his great-nephew. “I was around him a whole lot growing up,” he tells Gridiron. “He was a funny kid. Always runnin’ here and there. He was quick, always in and out of things. I’d play with him in the yard a little bit. He was always into sports. Football and basketball.”

His nephew – and Saquon’s father – Alibay was a boxer as well: “He got into some trouble when he was coming up. He could fight, even made Golden Gloves one time. He was pretty good. But he made some bad choices in his life and things caught up with him.”

Before Saquon was born, Alibay was a troublemaker. Involved with drugs from an early age, he spent a year in Rikers on a gun charge. “He told me he watched me fight when he was up there (in Rikers),” Iran adds. “Said it motivated him to fight again when he got out.” So what about Saquon? Could he have been a fighter instead of a football player? “Nah, he wasn’t into boxing too much,” he says slowly. Perhaps he’s choosing his words carefully. Or perhaps the fog of 100,000 blows to the head is having an effect. “Football was the gift God gave him, just like He gave me boxing. We all do the best with what we got.”

The two sports have plenty in common: the culture of the sweet science, the brand of mental and physical toughness, to dish out and receive pain, to exert yourself to your physical limit and beyond. That’s what Saquon fell in love with as a kid. He just chose pigskin over ring craft. “I could have boxed,” Barkley told USA Today in an interview last year. “I truly, truly believe that if I didn’t fall in love with football, I would’ve ended up being a boxer.” Iran laughs when we read that quote, but then tells us that, on his first carry in Pop Warner, Saquon was hit so hard that a tooth came out. “He got straight back up,” he says. “He liked being hit. But he liked running away from people more.”

“He told me that the next four or five years of his life would determine his next 40. You can understand why someone would want to make sure they got that right.”

To get to Coplay and Bob Warke Field, the Barkleys had to leave the Bronx. Saquon’s mother Tonya told USA Today that the area they lived in had become “drug-infested” and that the hallways of their block were “roaming with gangsters, even when you’re coming out of your apartment to go to work in the morning”. Alibay was back using drugs and Iran says there was a line-in-the-sand moment. “Tonya said she was leaving,” he tells Gridiron. “She said he could stay (in the Bronx) or they could leave as a family.”

So the Barkleys headed some two hours up I-78 to Pennsylvania and, in doing so, changed their futures forever. “They had space to run around. And my nephew… he got a new focus. He got off the drugs. And they never hid anythin’. I think that’s why they’re strong.”

Saquon began dominating at Hokendauqua, then headed to Whitehall High School – only to find the early days difficult. At 160lbs and without a proper gym routine, he struggled. On the brink of quitting, his father – who’d long contemplated what might have been were it not for a serious shoulder injury that sapped his punching power – gave his son some sage advice. “He told him ‘If you quit this, it’ll be easy to quit jobs, quit relationships, quit on your kids,” reveals Iran. “That’s why Saquon’s always in the game. He ain’t a quitter.”

As a sophomore, he started to bulk up and got extended playing time. Rutgers offered him a scholarship based on his JV tape alone. He accepted gleefully and would have been a Scarlet Knight were it not for Penn State head coach Bill O’Brien telling him that, under no circumstances, could he leave the state. It was a decision, says Nittany Lion legend Franco Harris, that Barkley struggled with.

“He’s such a great kid. I think he felt like he’d made a commitment to Rutgers and he didn’t want to go back on that,” NFL Hall-of-Famer Harris tells Gridiron from his home in Pittsburgh, where he won four Super Bowls. “I remember him telling me that it was one of the hardest things he’d ever had to do and that he felt wrong doing it. But he told me that the next four or five years of his life would determine his next 40. You can understand why someone would want to make sure they got that right.”

It proved a wise choice for Barkley and Penn State. For all the dark days of the sexual-abuse scandal were diminishing, the once-great university was crying out for someone, anyone, to resuscitate it. Up stepped Saquon.

“Saquon is the perfect representation of Penn State football and all the good it stands for. What this kid accomplished… wow!”

If ever an institution needed a clarion call, he delivered. To the tune of 59 touchdowns on the field and the perfect student of it. “I tell people the NCAA tried to shut us down,” says Harris. “They had us on our knees and were trying to smash us to the ground.” There’s anger in his voice as he reflects on the chapter that almost finished the school for good. “We were so fortunate that Bill O’Brien did what he did and held the programme together. And so fortunate that, when other players were de-committing from us, he managed to persuade Saquon that he could be part of something special. I think the kid truly believed in us and he helped put us back on the national stage.

“We’re back! And Saquon is the perfect representation of Penn State football and all the good it stands for. What this kid accomplished… wow! I think these have been the greatest and most important two years in Penn State history and Barkley… he was such a huge part of that. Wow.”

As NFL teams conclude their background checks on players up and down the country, there will be a rare consensus on the Nittany Lions star runner. They’ll discover something he’d vowed to achieve years earlier: to become a great player and a greater human being. “I would punch myself in the nuts many, many, many times to be able to draft him,” one assistant coach said at the combine. Another scout compared him to a superhero, saying: “After his last drill, I thought he was going to put on a cape and fly out of here.” And one GM told the NFL Network: “He checks off all of the boxes as a player, and he’s an exceptional character kid. It’s hard to find a hole in his game. He has every single trait that you want in a player. He’s about as perfect as they come at the position.”

So what does Harris think of Barkley on and of the field? “Hey, he’s a great player,” he says. “But it’s true what they say – he’s a better kid. You know, you watch him play the game and he’s aggressive and tough and physical and all these things, but then when you meet him, you wonder if it’s the same person because all that stuff gets thrown out of the window. He’s so respectful. You can tell he’s had a good upbringing. You know, a lot of times, life is about how you deal with people, and how you respect people. He’s a really good man. Just someone that makes you feel comfortable to be around.”

The snow is falling in Pittsburgh as Harris talks. Seven or eight inches in the last few hours, he surmises. The 68-year-old looks out of the window and tells us he has to dig out the cars. “So what sort of runner do you see when you watch him?” we ask. He pauses, long enough to make Gridiron think the line’s dropped off. Then he utters one word: “Wow.” And he’s off eulogising on a guy he clearly thinks is going to be a superstar on Sundays.

“I mean, he’s got it all,” enthuses Harris. “Instincts, he knows when to cut, when to jump…” He laughs as if not quite believing what he’s seeing in his mind’s eye. “There’s just this sixth sense the great ones have so they can get the job done and make it happen. And big plays… boy, he makes some big plays. Anyone can make four yards a carry, but Saquon can turn a game around.”

So are we right? Is he the best running back since Adrian Peterson? A generational talent? He thinks a while and then gives us an answer. But then he thinks some more and asks us not to use his first response, instead tempering exceptions a little. “Look, I’ll say this… I’m a huge fan of his. And I love the way he runs. With his talent and drive and determination and his work ethic, he’s going to be… he has so much potential and the ability to do unbelievably great things. Now it’s up to him to go and do it and I look forward to watching him.”

“It’s hard to measure heart. Impossible even. But, when you look back at Saquon’s early years, it’s easy to see how a family that hid nothing and made him responsible for everything forged the young man.”

On those long walks to and from practice and games, Alibay Barkley would carry an emergency asthma inhaler just in case his son needed it. His allergy had all but disappeared upon leaving the Bronx, but Alibay carried it anyway, just in case. They’d often talk football, the Jets, Curtis Martin and the stop-start genius of Barry Sanders.

They’d talk about how Saquon was almost called Tupac Shakur Barkley after his father’s love for the rapper. And they’d talk about the path that led them to rural Pennsylvania and the one that might lead them to somewhere very rare. It’s hard to measure heart. Impossible even. But, when you look back at Saquon Barkley’s early years, it’s easy to see how a family that hid nothing and made him responsible for everything forged the young man who stands tantalisingly close to the brink of NFL stardom.

This article originally appeared in Issue XXXVIII of Gridiron magazine back in 2018 – for individual editions or subscriptions, click HERE